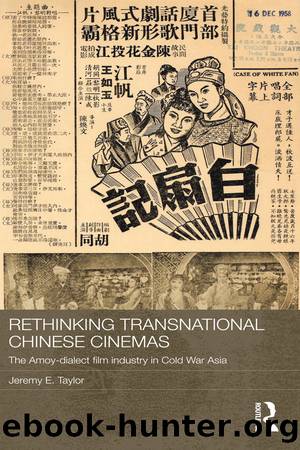

Rethinking Transnational Chinese Cinemas by Jeremy E. Taylor

Author:Jeremy E. Taylor [Taylor, Jeremy E.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: Social Science, Ethnic Studies, General, Media Studies

ISBN: 9780415728324

Google: _lzongEACAAJ

Publisher: Routledge

Published: 2013-10-25T05:05:13+00:00

âHong Kong is heavenâ

Even in the midst of such changes, however, certain elements of the ânew Amoy-dialect filmsâ suggested continuities with those that had been made earlier in the decade. Nowhere was this more obvious than in the spate of specifically Hong Kong-themed movies made from 1958 onwards.

In much the same vein as âsemi-colonialâ Shanghai had done in the prewar years, Hong Kong emerged as the single most important site for commercial cultural production and entertainment for many parts of the Chinese-speaking world in the 1950s. Contrary to popular belief, this was not restricted to Cantonese-speaking sections of the Chinese diaspora. It included communities whose historical links with Hong Kong and its Cantonese hinterland had always been minimal. As we saw earlier, Hong Kong emerged as the home of the Amoy-dialect film industry thanks to a unique combination of events and trends: the âfallâ of the mainland to communism in 1949 and the influx of a small but significant community of middle-class refugees from Fujian; an existing entertainment, media and financial infrastructure which made it the perfect place for businesspeople from other parts of the Chinese diaspora to invest; and a position at the crossroads between the major sites of Hokkien cultural production and consumption (i.e., South East Asia and Taiwan).

Yet until the re-invigoration of the industry from 1957 onwards one could be forgiven for thinking otherwise. In the vast majority of Amoy-dialect films prior to that year, little reference was ever made to Hong Kong itself. Hong Kongâs temples, parks and waterways certainly appeared in Amoy-dialect films, but only as approximations of the landscapes of âcultural Chinaâ and imperial Quanzhou, and rarely as twentieth-century Asia. In the ânewâ Amoy-dialect films, however, Hong Kong became more than just a space within which movies could be shot. The city itself came to star in many of the films. Indeed, despite the fact that its Hokkien-speaking community was demographically tiny in comparison to the Cantonese majority, Britainâs Chinese colony assumed a central place in the ânew Amoy-dialect filmsâ as film-makers portrayed it as a vibrant site of modernity for Hokkien speakers. Further, as film-makers made use of Hong Kong studios and streetscapes, and in line with a general sense in the 1950s that Hong Kong offered a âunique experience of opennessâ unmatched in many other parts of east and South East Asia at the time (Wang 1999: 126), the city came to be reinvented on the Amoy-dialect screen as a paragon of urban modernity.

Ironically, the reasons for this were typically Amoy-dialect. The industry may have benefited from the new influx of Singapore and Philippine money, but the budgetary habits it had developed in earlier years continued to shape Amoy-dialect film-making in the late 1950s. It was cheap and easy to film Hong Kong streetscapes when making a romantic comedy, crime thriller or melodrama about life in modern, urban Asia. And it was for this reason that films of this period would often begin with what might be described as on-screen travelogues of Hong Kong.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Exploring Deepfakes by Bryan Lyon and Matt Tora(8367)

Robo-Advisor with Python by Aki Ranin(8310)

Offensive Shellcode from Scratch by Rishalin Pillay(6428)

Microsoft 365 and SharePoint Online Cookbook by Gaurav Mahajan Sudeep Ghatak Nate Chamberlain Scott Brewster(5678)

Ego Is the Enemy by Ryan Holiday(5413)

Management Strategies for the Cloud Revolution: How Cloud Computing Is Transforming Business and Why You Can't Afford to Be Left Behind by Charles Babcock(4563)

Python for ArcGIS Pro by Silas Toms Bill Parker(4503)

Machine Learning at Scale with H2O by Gregory Keys | David Whiting(4292)

Elevating React Web Development with Gatsby by Samuel Larsen-Disney(4224)

Liar's Poker by Michael Lewis(3441)

Learning C# by Developing Games with Unity 2021 by Harrison Ferrone(3350)

Speed Up Your Python with Rust by Maxwell Flitton(3310)

OPNsense Beginner to Professional by Julio Cesar Bueno de Camargo(3283)

Extreme DAX by Michiel Rozema & Henk Vlootman(3263)

Agile Security Operations by Hinne Hettema(3190)

Linux Command Line and Shell Scripting Techniques by Vedran Dakic and Jasmin Redzepagic(3172)

Essential Cryptography for JavaScript Developers by Alessandro Segala(3144)

Cryptography Algorithms by Massimo Bertaccini(3084)

AI-Powered Commerce by Andy Pandharikar & Frederik Bussler(3052)